How to Design a Summing Amplifier Based on the Input and Output Voltage Level Requirements

In allaboutcircuits.com forum a member asked how can he drive a MOSFET that needs a voltage range of 4V to 5V with a DAC with the output range of 0V to 5V?

Initially I thought he should use a differential amplifier. However, based on the articles I published, MasteringElectronicsDesign.com: Solving the Differential Amplifier – Part 1, Part 2 and Part3 the solution based on a differential amplifier would require a negative voltage level in the input. Although V1 can be the input from 0V to 5V, V2 has to be negative, so that the output shifts to positive values.

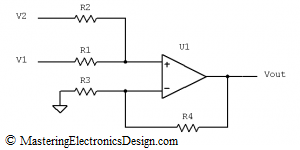

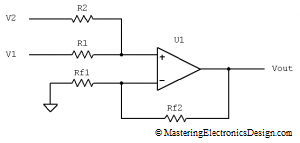

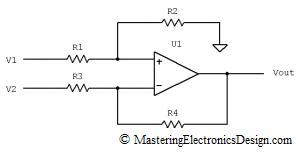

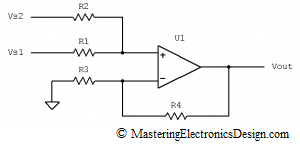

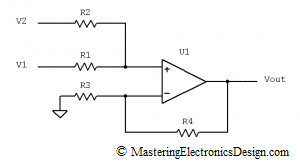

Then I thought of the Summing Amplifier, or the Non-Inverting Summing Amplifier, which is shown in Figure 1. It is called a summing amplifier, because two signals are summed in one of the amplifier inputs. In this case, V1 and V2 are summed in the non-inverting input.

Figure 1

Figure 1

The summing of V1 and V2 is not direct. Resistors R1 and R2 make a weighted sum and this is what makes this amplifier very useful. As in the case with the differential amplifier, one can use this circuit to achieve any linear function. This article shows you how to design a summing amplifier based on the input and output requirements. You can also solve your amplifier with the calculator I posted here: MasteringElectronicsDesign.com: Summing Amplifier Calculator.

The transfer function of the summing amplifier is as follows.

|

(1) |

You can find its demonstration in this article, MasteringElectronicsDesign.com: How to Derive the Summing Amplifier Transfer Function.

Let’s write down what we know:

If Vin1 = 0V then Vout1 = 4V and

If Vin2 = 5V then Vout2 = 5V,

where by Vin1 and Vin2 I noted the input range limits, and by Vout1 and Vout2 I noted the output range limits.

Let’s choose one of the summing amplifier inputs to be Vin, say V1.

Because we have two instances that we know, Vin1 and Vin2 and the corresponding outputs, Vout1 and Vout2, let’s rewrite equation (1) using these two instances.

|

(2) |

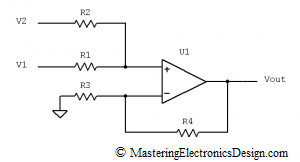

This is a linear system of two equations with a lot of unknowns: R1, R2, R3, R4 and V2. However, we can simplify our life by grouping the resistors in ratios. The equations can be rewritten like this,

|

(3) |

where by k1 and k2 I noted:

|

(4) |

Now we are left with three unknowns, k1, k2, V2. I can simply consider V2 as a known value, because I can connect to R2 any voltage I want or, more conveniently, a voltage that I already have in the circuit. I will target for V2 = 5V, since there is already a DAC in this circuit with an output range of 0 to 5V. So I can assume there is a 5V reference in this circuit.

If k1 and k2 are the remaining unknowns, then (3) is a system of two equations and two unknowns as in (5), which can be easily solved.

|

(5) |

It can be easily seen that the second equation becomes

|

(6) |

so k2 has to be zero.

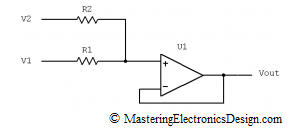

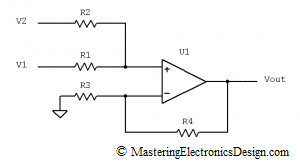

The result is k1 = 1/4 and k2 = 0.

This result shows that we do not need the resistors R3 and R4. Also, the ratio between R2 and R1 is 1/4. We can choose R2 = 1 kohm and a standard value for R1 = 4.02 kohm with a 1% tolerance.

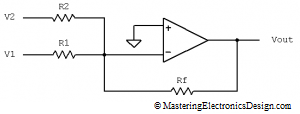

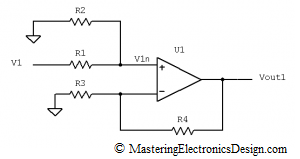

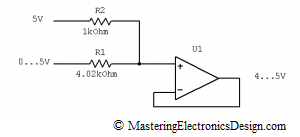

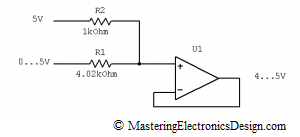

The final circuit is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Since k2 is zero, R3 is zero, configuring U1 as a repeater for the summed voltage in the non inverting input.