The summing amplifier, or the non-inverting summing amplifier, is an analog processing circuit with the transfer function (the summing amplifier formula as some say) shown in the following equation.

|

(1) |

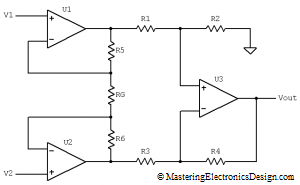

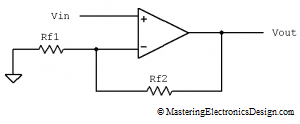

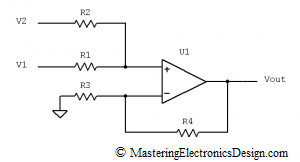

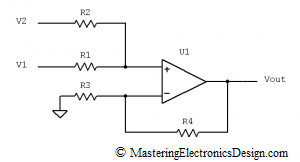

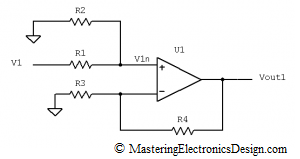

The first term of the product is the actual summing, while the second term is a gain due to the R3 and R4 resistors. I prefer this type of summing amplifier as shown in Figure 1, because it is more flexible and allows us to achieve any linear function we want.

Figure 1

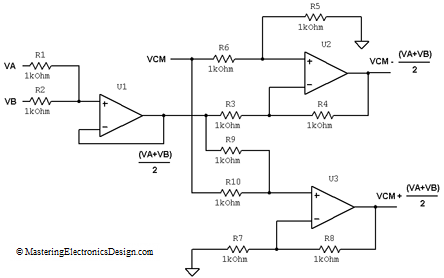

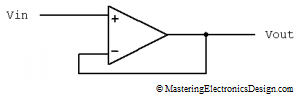

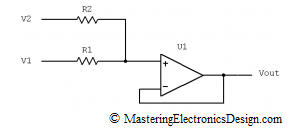

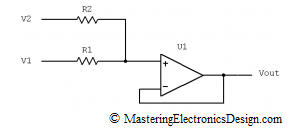

Some authors prefer the following schematic,

Figure 2

with the transfer function

|

(2) |

One can see that the summing amplifier in Figure 2 is a subset of my preferred schematic in Figure 1. In Figure 2, R4 is zero, while R3 is infinity (open connection). It performs the analog summation between V1 and V2, with a gain of 1. Therefore, the amplifier in Figure 1 gives us more choices when designing a function with this circuit. If the gain is not needed, this should come up from calculations, as in this article Solving the Summing Amplifier.

If you followed this website, by now you probably figured that I am not a promoter of learning formulas by heart. I like to derive the transfer function if I need it. So, how do we prove this formula?

We will use the Superposition Theorem, which says that, the effect of all the sources in a circuit is equal with the sum of the effects of each source taken separately in the same circuit. Therefore, if we take out one source, V2, and replace it with a wire, we then can find the voltage in each node and the current in each branch of this circuit due to the remaining source V1. Then we do the same with V1 and then sum up the currents on each branch and the voltage levels on each node. We are only interested in Vout, so this should be simple.

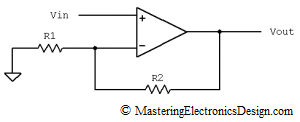

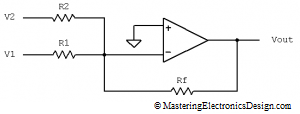

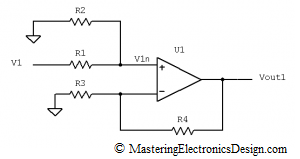

We will first make V2 = 0V, by connecting R2 to ground, as in Figure 3.

Figure 3

The Op Amp is considered an ideal component, so that the input bias currents are negligible. If the current in the non-inverting input is zero, R1 and R2 make a voltage divider for V1. The non-inverting input voltage V1n, can be written as

|

(3) |

and, based on the non-inverting amplifier transfer function, Vout1 is

|

(4) |

By replacing V1n in (4), the output voltage is

|

(5) |

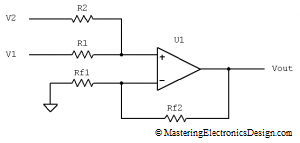

In the second part of my demonstration, based on the Superposition Theorem, R2 is connected back to V2 and V1 = 0, by connecting R1 to ground. Following the same train of thought Vout2 can be written as

|

(6) |

Now we have to add Vout1 to Vout2 to complete the third step of the Superposition Theorem. After factorizing the gain component 1+R4/R3, the summing amplifier transfer function becomes the mathematical relation shown in (7).

|

(7) |

Q.E.D.

>>> <<<

This formula shows that this sum is a weighted sum between V1 and V2. This is better than a direct sum V1 plus V2, because, again, brings flexibility in design. Together with the differential amplifier, this circuit brings another treat in the art of electronics design.